The Silence After the Mud

Brazil's Fundão dam collapse

Al Jazeera

Brazil, 2016

Written by: Ingrid Fadnes

Photographs by: Fábio Nascimento

On November 5, 2015, the Fundao dam burst in the inland municipality of Mariana in the Brazilian state of Minas Gerais. The Brazilian mining company Samarco, owned by two of the world’s biggest mining corporations, Vale SA and BHP Billiton, operated the dam.

Tcharly do Barmo Batista, a 23-year-old father, closes his eyes as he recalls the mud tsunami that swept away half his village, Paracatu de Baixo.

“We could hear the mud bursting down the valley. It took my house, the football field, the church, the local bar, my neighbours’ houses.

“And then there was silence.”

Batista is one of thousands affected by the burst dam. All along the river, people are asking more questions than the companies are willing to answer.

By the end of February, Samarco’s president, Ricardo Vescovi, and five other officials had been put under investigation for environmental crimes. At the beginning of May, eight more officials from the company were put under review. The company had been warned about the dam several times and advised to increase monitoring of it and to reinforce it with a buttress, but Samarco did not follow the recommendations.

The trial against Samarco has now stopped after the three companies involved, Samarco, Vale SA and BHP Billiton, signed a compensation agreement. Over the course of 15 years, they will repair damage amounting to almost $5.6bn.

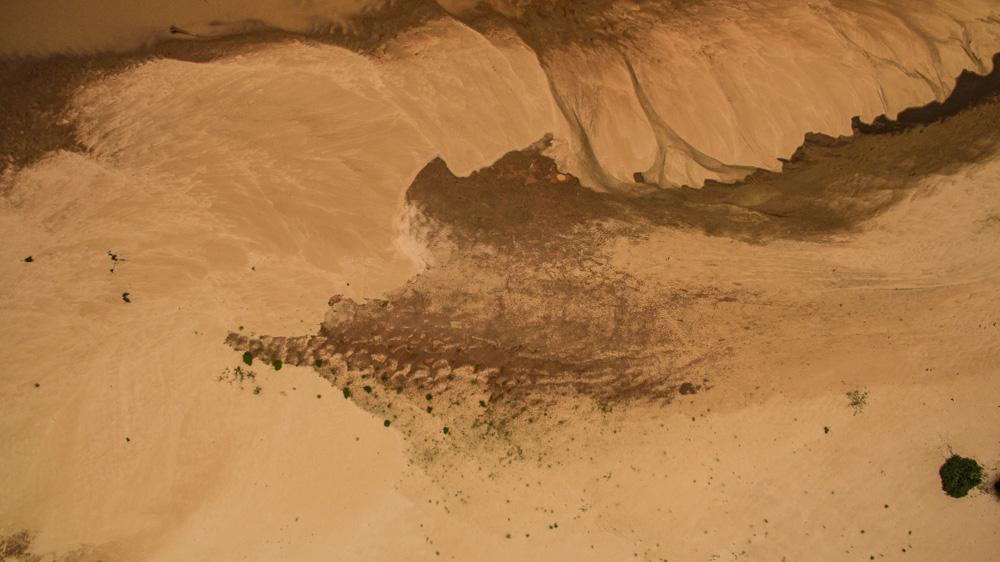

When the dam collapsed, a three-metre mud wave consisting of 62 million cubic-metres of mining waste stormed down the valley, heading for the small town of Bento Rodrigues a few kilometres away.

“I drove as fast as I could towards Bento Rodrigues, but the roads were closed. No one was allowed in or out. I was in complete despair and thought that I would never see my family again,” says one witness to the disaster, Expedito.

He shakes his head and clutches his coffee cup as he sits in the kitchen of his new accommodation – temporarily allotted to his family by Samarco.

“It was a completely normal day,” adds his wife, Roselene, who was at the school where she works as a teacher when the dam collapsed. “Suddenly, someone came running in through the door of the school yelling, ‘Gather all the children and run towards higher ground.'”

Massive outpourings of mining sludge killed 13 workers at the dam when it burst and collapsed. Still, the company didn’t issue an evacuation notice for the village of Bento Rodrigues that lay in the path of the toxic waves.

When the mud thundered in over Bento Rodrigues, five people were dragged off by the powerful wave, three of them children.

“There was time. There was time to evacuate everyone, had only the warning come,” claims Expedito. The relief of finding his family alive initially overrided concerns about their future and the total loss of their possessions. But today, Expedito’s sighs deepen as he looks around the empty kitchen.

“We don’t know how long we will be here. We don’t know if the town can be rebuilt. We don’t know if we have to stay here in the city or what is waiting for us.”